Early Life among the Indians: Chapter II

March 21, 2018

By Amorin Mello

Early life among the Indians

by Benjamin Green Armstrong

continued from Chapter I.

CHAPTER II

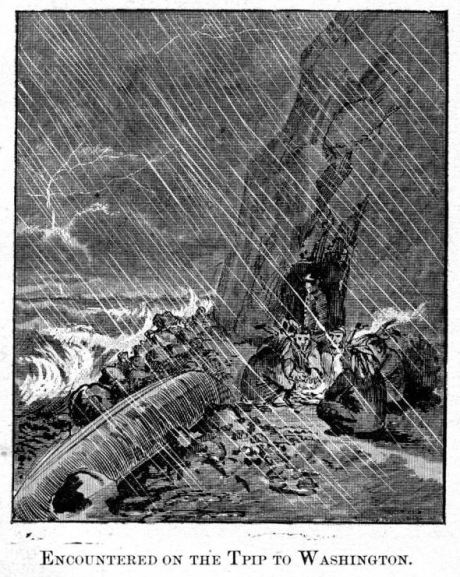

In Washington.—Told to Go Home.—Senator Briggs, of New York.—The Interviews with President Fillmore.—Reversal of the Removal Order.—The Trip Home.—Treaty of 1854 and the Reservations.—The Mile Square.—The Blinding. »

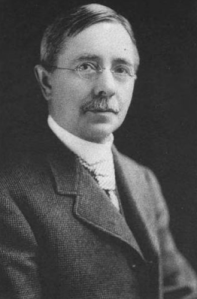

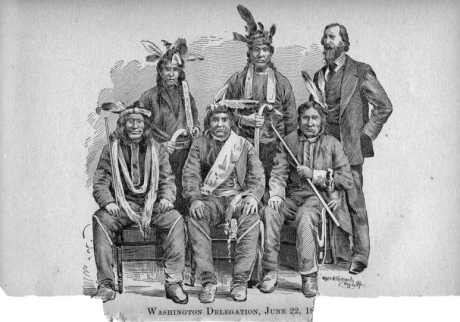

After a fey days more in New York City I had raised the necessary funds to redeem the trinkets pledged with the ‘bus driver and to pay my hotel bills, etc., and on the 22d day of June, 1852, we had the good fortune to arrive in Washington.

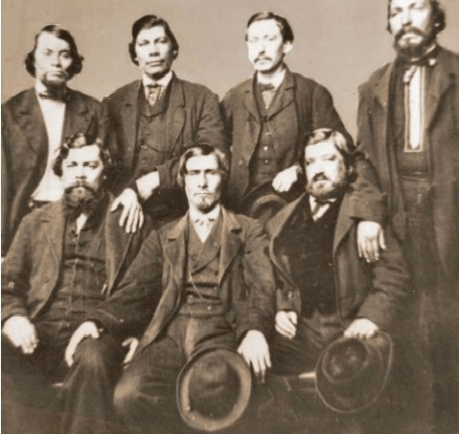

“Washington Delegation, June 22, 1852“

Engraved from an unknown photograph by Marr and Richards Co. for Benjamin Armstrong’s Early Life Among the Indians. Chief Buffalo, his speaker Oshogay, Vincent Roy, Jr., two other La Pointe Band members, and Armstrong are assumed to be in this engraving.

I took my party to the Metropolitan Hotel and engaged a room on the first floor near the office for the Indians, as they said they did not like to get up to high in a white man’s house. As they required but a couple mattresses for their lodgings they were soon made comfortable. I requested the steward to serve their meals in their room, as I did not wish to take them into the dining room among distinguished people, and their meals were thus served.

Undated postcard of the Metropolitan Hotel, formerly known as Brown’s India Queen Hotel.

~ StreetsOfWashington.com

The morning following our arrival I set out in search of the Interior Department of the Government to find the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, to request an interview with him, which he declined to grant and said :

“I want you to take your Indians away on the next train west, as they have come here without permission, and I do not want to see you or hear of your Indians again.”

I undertook to make explanations, but he would not listen to me and ordered me from his office. I went to the sidewalk completely discouraged, for my present means was insufficient to take them home. I paced up and down the sidewalk pondering over what was best to do, when a gentleman came along and of him I inquired the way to the office of the Secretary of the Interior. He passed right along saying,

Secretary of the Interior

Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart

~ Department of the Interior

“This way, sir; this way, sir;” and I followed him.

He entered a side door just back of the Indian Commissioner’s office and up a short flight of stairs, and going in behind a railing, divested himself of hat and cane, and said :

“What can I do for you sir.”

I told him who I was, what my party consisted of, where we came from and the object of our visit, as briefly as possible. He replied that I must go and see the Commissioner of Indian Affairs just down stairs. I told him I had been there and the treatment I had received at his hands, then he said :

“Did you have permission to come, and why did you not go to your agent in the west for permission?”

I then attempted to explain that we had been to the agent, but could get no satisfaction; but he stopped me in the middle of my explanation, saying :

“I can do nothing for you. You must go to the Indian Commissioner,”

and turning, began a conversation with his clerk who was there when we went in.

I walked out more discouraged than ever and could not imagine what next I could do. I wandered around the city and to the Capitol, thinking I might find some one I had seen before, but in this I failed and returned to the hotel, where, in the office I found Buffalo surrounded by a crowd who were trying to make him understand them and among them was the steward of the house. On my entering the office and Buffalo recognizing me, the assemblage, seeing I knew him, turned their attention to me, asking who he was, etc., to all of which questions I answered as briefly as possible, by stating that he was the head chief of of the Chippewas of the Northwest. The steward then asked:

“Why don’t you take him into the dining room with you? Certainly such a distinguished man as he, the head of the Chippewa people, should have at least that privilege.”

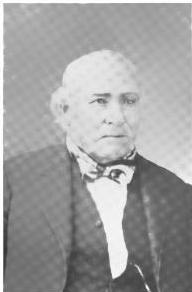

United States Representative George Briggs

~ Library of Congress

I did so and as we passed into the dining room we were shown to a table in one corner of the room which was unoccupied. We had only been seated a few moments when a couple of gentlemen who had been occupying seats in another part of the dining room came over and sat at our table and said that if there were no objections they would like to talk with us. They asked about the party, where from, the object of the visit, etc. I answered them briefly, supposing them to be reporters and I did not care to give them too much information. One of these gentlemen asked what room we had, saying that himself and one or two others would like to call on us right after dinner. I directed them where to come and said I would be there to meet them.

About 2 o’clock they came, and then for the first time I knew who those gentlemen were. One was Senator Briggs, of New York, and the others were members of President Filmore’s cabinet, and after I had told them more fully what had taken me there, and the difficulties I had met with, and they had consulted a little while aside. Senator Briggs said :

“We will undertake to get you and your people an interview with the President, and will notify you here when a meeting can be arranged. ”

During the afternoon I was notified that an interview had been arranged for the next afternoon at 3 o’clock. During the evening Senator Briggs and other friends called, and the whole matter was talked over and preparations made for the interview the following day, which were continued the next day until the hour set for the interview.

United States President

Millard Fillmore.

~ Library of Congress

When we were assembled Buffalo’s first request was that all be seated, as he had the pipe of peace to present, and hoped that all who were present would partake of smoke from the peace pipe. The pipe, a new one brought for the purpose, was filled and lighted by Buffalo and passed to the President who took two or three draughts from it, and smiling said, “Who is the next?” at which Buffalo pointed out Senator Briggs and desired he should be the next. The Senator smoked and the pipe was passed to me and others, including the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Secretary of the Interior and several others whose names I did not learn or cannot recall. From them, to Buffalo, then to O-sho-ga, and from him to the four braves in turn, which completed that part of the ceremony. The pipe was then taken from the stem and handed to me for safe keeping, never to be used again on any occasion. I have the pipe still in my possession and the instructions of Buffalo have been faithfully kept. The old chief now rose from his seat, the balance following his example and marched in single file to the President and the general hand-shaking that was began with the President was continued by the Indians with all those present. This over Buffalo said his under chief, O-sha-ga, would state the object of our visit and he hoped the great father would give them some guarantee that would quiet the excitement in his country and keep his young men peaceable. After I had this speech thoroughly interpreted, O-sha-ga began and spoke for nearly an hour. He began with the treaty of 1837 and showed plainly what the Indians understood the treaty to be. He next took up the treaty of 1842 and said he did not understand that in either treaty they had ceded away the land and he further understood in both cases that the Indians were never to be asked to remove from the lands included in those treaties, provided they were peaceable and behaved themselves and this they had done. When the order to move came Chief Buffalo sent runners out in all directions to seek for reasons and causes for the order, but all those men returned without finding a single reason among all the Superior and Mississippi Indians why the great father had become displeased. When O-sha-ga had finished his speech I presented the petition I had brought and quickly discovered that the President did recognize some names upon it, which gave me new courage. When the reading and examination of it had been concluded the meeting was adjourned, the President directing the Indian Commissioner to say to the landlord at the hotel that our hotel bills would be paid by the government. He also directed that we were to have the freedom of the city for a week.

Read Biographical Sketch of Vincent Roy, Jr. manuscript for a different perspective on their meeting the President.

The second day following this Senator Briggs informed me that the President desired another interview that day, in accordance with which request we went to the White House soon after dinner and meeting the President, he told the, delegation in a brief speech that he would countermand the removal order and that the annuity payments would be made at La Pointe as before and hoped that in the future there would be no further cause for complaint. At this he handed to Buffalo a written instrument which he said would explain to his people when interpreted the promises he had made as to the removal order and payment of annuities at La Pointe and hoped when he had returned home he would call his chiefs together and have all the statements therein contained explained fully to them as the words of their great father at Washington.

The reader can imagine the great load that was then removed from my shoulders for it was a pleasing termination of the long and tedious struggle I had made in behalf of the untutored but trustworthy savage.

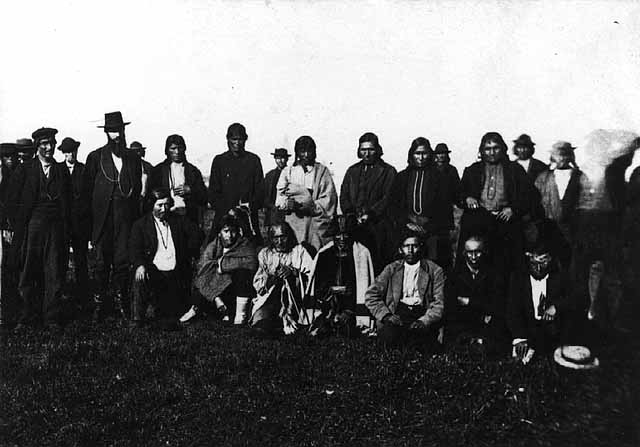

On June 28th, 1852, we started on our return trip, going by cars to La Crosse, Wis., thence by steamboat to St. Paul, thence by Indian trail across the country to Lake Superior. On our way from St. Paul we frequently met bands of Indians of the Chippewa tribe to whom we explained our mission and its results, which caused great rejoicing, and before leaving these bands Buffalo would tell their chief to send a delegation, at the expiration of two moons, to meet him in grand council at La Pointe, for there was many things he wanted to say to them about what he had seen and the nice manner in which he had been received and treated by the great father.

At the time appointed by Buffalo for the grand council at La Pointe, the delegates assembled and the message given Buffalo by President Filmore was interpreted, which gave the Indians great satisfaction. Before the grand council adjourned word was received that their annuities would be given to them at La Pointe about the middle of October, thus giving them time to get together to receive them. A number of messengers was immediately sent out to all parts of the territory to notify them and by the time the goods arrived, which was about October 15th, the remainder of the Indians had congregated at La Pointe. On that date the Indians were enrolled and the annuities paid and the most perfect satisfaction was apparent among all concerned. The jubilee that was held to express their gratitude to the delegation that had secured a countermanding order in the removal matter was almost extravagantly profuse. The letter of the great father was explained to them all during the progress of the annuity payments and Chief Buffalo explained to the convention what he had seen; how the pipe of peace had been smoked in the great father’s wigwam and as that pipe was the only emblem and reminder of their duties yet to come in keeping peace with his white children, he requested that the pipe be retained by me. He then went on and said that there was yet one more treaty to be made with the great father and he hoped in making it they would be more careful and wise than they had heretofore been and reserve a part of their land for themselves and their children. It was here that he told his people that he had selected and adopted, me as his son and that I would hereafter look to treaty matters and see that in the next treaty they did not sell them selves out and become homeless ; that as he was getting old and must soon leave his entire cares to others, he hoped they would listen to me as his confidence in his adopted son was great and that when treaties were presented for them to sign they would listen to me and follow my advice, assuring them that in doing so they would not again be deceived.

Map of Lake Superior Chippewa territories ceded in 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854.

~ Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission

After this gathering of the Indians there was not much of interest in the Indian country that I can recall until the next annual payment in 1853. This payment was made at La Pointe and the Indians had been notified that commissioners would be appointed to make another treaty with them for the remainder of their territory. This was the territory lying in Minnesota west of Lake Superior; also east and west of the Mississippi river north to the territory belonging to the Boisfort and Pillager tribe, who are a part of the Chippewa nation, but through some arrangement between themselves, were detached from the main or more numerous body. It was at this payment that the Chippewa Indians proper desired to have one dollar each taken from their annuities to recompense me for the trouble and expense I had been to on the trip to Washington in their behalf, but I refused to accept it by reason of their very impecunious condition.

It was sometime in August, 1854, before the commissioners arrived at LaPointe to make the treaty and pay the annuities of that year. Messengers were despatched to notify all Indians of the fact that the great father had sent for them to come to La Pointe to get their money and clothing and to meet the government commissioners who wished to make another treaty with them for the territory lying west of Lake Superior and they were further instructed to have the Indians council among themselves before starting that those who came could be able to tell the wishes of any that might remain away in regards to a further treaty and disposition of their lands. Representatives came from all parts of the Chippewa country and showed a willingness to treat away the balance of their country. Henry C. Gilbert, the Indian agent at La Pointe, formerly of Ohio, and David B. Herriman, the agent for the Chippewas of the Mississippi country, were the commissioners appointed by the government to consumate this treaty.

While we were waiting the arrival of the interior Indians I had frequent talks with the commissioners and learned what their instructions were and about what they intended to offer for the lands which information I would communicate to Chief Buffalo and other head men in our immediate vicinity, and ample time was had to perfect our plans before the others should arrive, and when they did put in an appearance we were ready to submit to them our views for approval or rejection. Knowing as I did the Indians’ unwillingness to give up and forsake their old burying grounds I would not agree to any proposition that would take away the remainder of their lands without a reserve sufficient to afford them homes for themselves and posterity, and as fast as they arrived I counselled with them upon this subject and to ascertain where they preferred these reserves to be located. The scheme being a new one to them it required time and much talk to get the matter before them in its proper light. Finally it was agreed by all before the meeting of the council that no one would sign a treaty that did not give them reservations at different points of the country that would suit their convenience, that should afterwards be considered their bona-fide home. Maps were drawn of the different tracts that had been selected by the various chiefs for their reserve and permanent home. The reservations were as follows :

One at L’Anse Bay, one at Ontonagon, one at Lac Flambeau, one at Court O’Rilles, one at Bad River, one at Red Cliff or Buffalo Bay, one at Fond du Lac, Minn., and one at Grand Portage, Minn.

Joseph Stoddard (photo c.1941) worked on the 1854 survey of the Bad River Reservation exterior boundaries, and shared a different perspective about these surveys.

~ Bad River Tribal Historic Preservation Office

The boundaries were to be as near as possible by metes and bounds or waterways and courses. This was all agreed to by the Lake Superior Indians before the Mississippi Chippewas arrived and was to be brought up in the general council after they had come in, but when they arrived they were accompanied by the American Fur Company and most of their employees, and we found it impossible to get them to agree to any of our plans or to come to any terms. A proposition was made by Buffalo when all were gathered in council by themselves that as they could not agree as they were, a division should be drawn, dividing the Mississippi and the Lake Superior Indians from each other altogether and each make their own treaty After several days of counselling the proposition was agreed to, and thus the Lake Superiors were left to make their treaty for the lands mouth of Lake Superior to the Mississippi and the Mississippis to make their treaty for the lands west of the Mississippi. The council lasted several days, as I have stated, which was owing to the opposition of the American Fur Company, who were evidently opposed to having any such division made ; they yielded however, but only when they saw further opposition would not avail and the proposition of Buffalo became an Indian law. Our side was now ready to treat with the commissioners in open council. Buffalo, myself and several chiefs called upon them and briefly stated our case but were informed that they had no instructions to make any such treaty with us and were only instructed to buy such territory as the Lake Superiors and Mississippis then owned. Then we told them of the division the Indians had agreed upon and that we would make our own treaty, and after several days they agreed to set us off the reservations as previously asked for and to guarantee that all lands embraced within those boundaries should belong to the Indians and that they would pay them a nominal sum for the remainder of their possessions on the north shores. It was further agreed that the Lake Superior Indians should have two- thirds of all money appropriated for the Chippewas and the Mississippi contingent the other third. The Lake Superior Indians did not seem, through all these councils, to care so much for future annuities either in money or goods as they did for securing a home for themselves and their posterity that should be a permanent one. They also reserved a tract of land embracing about 100 acres lying across and along the Eastern end of La Pointe or Madeline Island so that they would not be cut off from the fishing privilege.

It was about in the midst of the councils leading up to the treaty of 1854 that Buffalo stated to his chiefs that I had rendered them services in the past that should be rewarded by something more substantial than their thanks and good wishes, and that at different times the Indians had agreed to reward me from their annuity money but I had always refused such offers as it would be taking from their necessities and as they had had no annuity money for the two years prior to 1852 they could not well afford to pay me in this way.

“And now,” continued Buffalo, “I have a proposition to make to you. As he has provided us and our children with homes by getting these reservations set off for us, and as we are about to part with all the lands we possess, I have it in my power, with your consent, to provide him with a future home by giving him a piece of ground which we are about to part with. He has agreed to accept this as it will take nothing from us and makes no difference with the great father whether we reserve a small tract of our territory or not, and if you agree I will proceed with him to the head of the lake and there select the piece of ground I desire him to have, that it may appear on paper when the treaty has been completed.”

The chiefs were unanimous in their acceptance of the proposition and told Buffalo to select a large piece that his children might also have a home in future as has been provided for ours.

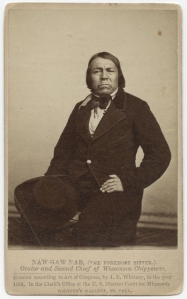

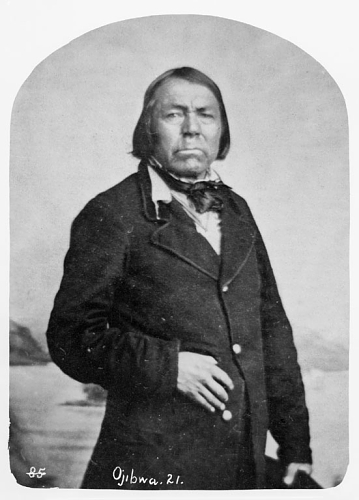

Kiskitawag (Giishkitawag: “Cut Ear”) signed earlier treaties as a warrior of the Ontonagon Band and became associated with the La Pointe Band at Odanah.

~C.M. Bell, Smithsonian Digital Collections

This council lasted all night and just at break of day the old chief and myself, with four braves to row the boat, set out for the head of Lake Superior and did not stop anywhere only long enough to make and drink some tea, until we reached the head of St. Louis Bay. We landed our canoe by the side of a flat rock quite a distance from the shore, among grass and rushes. Here we ate our lunch and when completed Buffalo and myself, with another chief, Kish-ki-to-uk, waded ashore and ascended the bank to a small level plateau where we could get a better view of the bay. Here Buffalo turned to me, saying: .

“Are you satisfied with this location? I want to reserve the shore of this bay from the mouth of St. Louis river. How far that way do you you want it to go?” pointing southeast, or along the south shore of the lake.

I told him we had better not try to make it too large for if we did the great father’s officers at Washington might throw it out of the treaty and said:

“I will be satisfied with one mile square, and let it start from the rock which we have christened Buffalo rock, running easterly in the direction of Minnesota Point, taking in a mile square immediately northerly from the head of St. Louis Bay”

As there was no other way of describing it than by metes and bounds we tried to so describe it in the treaty, but Agent Gilbert, whether by mistake or not I am unable to say, described it differently. He described it as follows: “Starting from a rock immediately above and adjoining Minnesota Point, etc.”

We spent an hour or two here in looking over the plateau then went back to our canoe and set out for La Pointe. We traveled night and day until we reached home.

During our absence some of the chiefs had been talking more or less with the commissioners and immediately on our return all the Indians met in a grand council when Buffalo explained to them what he had done on the trip and how and where he had selected the piece of land that I was to have reserved in the treaty for my future home and in payment for the services I had rendered them in the past. The balance of the night was spent in preparing ourselves for the meeting with the treaty makers the next day, and about 10 o’clock next morning we were in attendance before the commissioners all prepared for a big council.

Agent Gilbert started the business by beginning a speech interpreted by the government interpreter, when Buffalo interrupted him by saying that he did not want anything interpreted to them from the English language by any one except his adoped son for there had always been things told to the Indians in the past that proved afterwards to be untrue, whether wrongly interpreted or not, he could not say;

“and as we now feel that my adopted son interprets to us just what you say, and we can get it correctly, we wish to hear your words repeated by him, and when we talk to you our words can be interpreted by your own interpreter, and in this way one interpreter can watch the other and correct each other should there be mistakes. We do not want to be deceived any more as we have in the past. We now understand that we are selling our lands as well as the timber and that the whole, with the exception of what we shall reserve, goes to the great father forever.”

Commissioner of Indian affairs. Col. Manypenny, then said to Buffalo:

“What you have said meets my own views exactly and I will now appoint your adopted son your interpreter and John Johnson, of Sault Ste. Marie, shall be the interpreter on the part of the government,” then turning to the commissioners said, “how does that suit you, gentlemen.”

They at once gave their consent and the council proceeded.

Buffalo informed the commissioners of what he had done in regard to selecting a tract of land for me and insisted that it become a part of the treaty and that it should be patented to me directly by the government without any restrictions. Many other questions were debated at this session but no definite agreements were reached and the council was adjourned in the middle of the afternoon. Chief Buffalo asking for the adjournment that he might talk over some matters further with his people, and that night the subject of providing homes for their half-breed relations who lived in different parts of the country was brought up and discussed and all were in favor of making such a provision in the treaty. I proposed to them that as we had made provisions for ourselves and children it would be only fair that an arrangement should be made in the treaty whereby the government should provide for our mixed blood relations by giving to each person the head of a family or to each single person twenty-one years of age a piece of land containing at least eighty acres which would provide homes for those now living and in the future there would be ample room on the reservations for their children, where all could live happily together. We also asked that all teachers and traders in the ceded territory who at that time were located there by license and doing business by authority of law, should each be entitled to 160 acres of land at $1.25 per acre. This was all reduced to writing and when the council met next morning we were prepared to submit all our plans and requests to the commissioners save one, which we required more time to consider. Most of this day was consumed in speech-making by the chiefs and commissioners and in the last speech of the day, which was made by Mr. Gilbert, he said:

“We have talked a great deal and evidently understand one another. You have told us what you want, and now we want time to consider your requests, while you want time as you say to consider another matter, and so we will adjourn until tomorrow and we, with your father. Col. Manypenny, will carefully examine and consider your propositions and when we meet to-morrow we will be prepared to answer you with an approval or rejection.”

Julius Austrian purchased the village of La Pointe and other interests from the American Fur Company in 1853. He entered his Town Plan of La Pointe on August 29th of 1854. He was the highest paid claimant of the 1854 Treaty at La Pointe. His family hosted the 1855 Annuity Payments at La Pointe.

~ Photograph of Austrian from the Madeline Island Museum

That evening the chiefs considered the other matter, which was to provide for the payment of the debts of the Indians owing the American Fur Company and other traders and agreed that the entire debt could not be more than $90,000 and that that amount should be taken from the Indians in bulk and divided up among their creditors in a pro-rata manner according to the amount due to any person or firm, and that this should wipe out their indebtedness. The American Fur Company had filed claims which, in the aggregate, amounted to two or three times this sum and were at the council heavily armed for the purpose of enforcing their claim by intimidation. This and the next day were spent in speeches pro and con but nothing was effected toward a final settlement.

Col. Manypenny came to my store and we had a long private interview relating to the treaty then under consideration and he thought that the demands of the Indians were reasonable and just and that they would be accepted by the commissioners. He also gave me considerable credit for the manner in which I had conducted the matter for Indians, considering the terrible opposition I had to contend with. He said he had claims in his possession which had been filed by the traders that amounted to a large sum but did not state the amount. As he saw the Indians had every confidence in me and their demands were reasonable he could see no reason why the treaty could not be speedily brought to a close. He then asked if I kept a set of books. I told him I only kept a day book or blotter showing the amount each Indian owed me. I got the books and told him to take them along with him and that he or his interpreter might question any Indian whose name appeared thereon as being indebted to me and I would accept whatever that Indian said he owed me whether it be one dollar or ten cents. He said he would be pleased to take the books along and I wrapped them up and went with him to his office, where I left them. He said he was certain that some traders were making claims for far more than was due them. Messrs. Gilbert and Herriman and their chief clerk, Mr. Smith, were present when Mr. Manypenny related the talk he had with me at the store. He considered the requests of the Indians fair and just, he said, and he hoped there would be no further delays in concluding the treaty and if it was drawn up and signed with the stipulations and agreements that were now understood should be incorporated in it, he would strongly recommend its ratification by the President and senate.

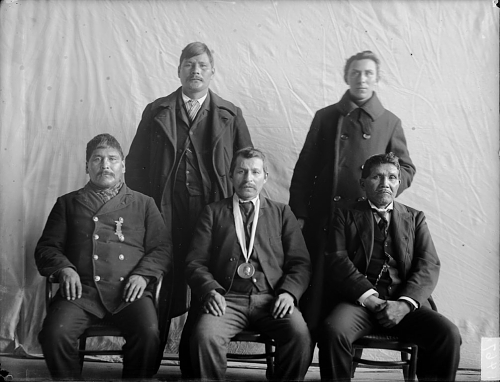

Naagaanab of Fond Du Lac

~ Minnesota Historical Society

The day following the council was opened by a speech from Chief Na-gon-ab in which he cited considerable history.

“My friends,” he said, “I have been chosen by our chief, Buffalo, to speak to you. Our wishes are now on paper before you. Before this it was not so. We have been many times deceived. We had no one to look out for us. The great father’s officers made marks on paper with black liquor and quill. The Indian can not do this. We depend upon our memory. We have nothing else to look to. We talk often together and keep your words clear in our minds. When you talk we all listen, then we talk it over many times. In this way it is always fresh with us. This is the way we must keep our record. In 1837 we were asked to sell our timber and minerals. In 1842 we were asked to do the same. Our white brothers told us the great father did not want the land. We should keep it to hunt on. Bye and bye we were told to go away; to go and leave our friends that were buried yesterday. Then we asked each other what it meant. Does the great father tell the truth? Does he keep his promises? We cannot help ourselves! We try to do as we agree in treaty. We ask you what this means? You do not tell from memory! You go to your black marks and say this is what those men put down; this is what they said when they made the treaty. The men we talk with don’t come back; they do not come and you tell us they did not tell us so! We ask you where they are? You say you do not know or that they are dead and gone. This is what they told you; this is what they done. Now we have a friend who can make black marks on paper When the council is over he will tell us what we have done. We know now what we are doing! If we get what we ask our chiefs will touch the pen, but if not we will not touch it. I am told by our chief to tell you this: We will not touch the pen unless our friend says the paper is all right.”

Na-gon-ab was answered by Commissioner Gilbert, saying:

“You have submitted through your friend and interpreter the terms and conditions upon which you will cede away your lands. We have not had time to give them all consideration and want a little more time as we did not know last night what your last proposition would be. Your father. Col. Manypenny, has ordered some beef cattle killed and a supply of provisions will be issued to you right away. You can now return to your lodges and get a good dinner and talk matters over among yourselves the remainder of the day and I hope you will come back tomorrow feeling good natured and happy, for your father, Col. Manypenny, will have something to say to you and will have a paper which your friend can read and explain to you.”

When the council met next day in front of the commissioners’ office to hear what Col. Manypenny had to say a general good feeling prevailed and a hand-shaking all round preceded the council, which Col. Manypenny opened by saying:

“My friends and children: I am glad to see you all this morning looking good natured and happy and as if you could sit here and listen to what I have to say. We have a paper here for your friend to examine to see if it meets your approval. Myself and the commissioners which your great father has sent here have duly considered all your requests and have concluded to accept them. As the season is passing away and we are all anxious to go to our families and you to your homes, I hope when you read this treaty you will find it as you expect to and according to the understandings we have had during the council. Now your friend may examine the paper and while he is doing so we will take a recess until afternoon.”

Chief Buffalo, turning to me, said:

“My son, we, the chiefs of all the country, have placed this matter entirely in your hands. Go and examine the paper and if it suits you it will suit us.”

Then turning to the chiefs, he asked,

“what do you all say to that?”

The ho-ho that followed showed the entire circle were satisfied.

I went carefully through the treaty as it had been prepared and with a few exceptions found it was right. I called the attention of the commissioners to certain parts of the stipulations that were incorrect and they directed the clerk to make the changes.

The following day the Indians told the commissioners that as their friend had made objections to the treaty as it was they requested that I might again examine it before proceeding further with the council. On this examination I found that changes had been made but on sheets of paper not attached to the body of the instrument, and as these sheets contained some of the most important items in the treaty, I again objected and told the commissioners that I would not allow the Indians to sign it in that shape and not until the whole treaty was re-written and the detached portions appeared in their proper places. I walked out and told the Indians that the treaty was not yet ready to sign and they gave up all further endeavors until next day. I met the commissioners alone in their office that afternoon and explained the objectionable points in the treaty and told them the Indians were already to sign as soon as those objections were removed. They were soon at work putting the instrument in shape.

“One version of the boundaries for Chief Buffalo’s reservation is shown at the base of Minnesota Point in a detail from an 1857 map preserved in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Other maps show a larger and more irregularly shaped versions of the reservation boundary, though centered on the same area.”

~ DuluthStories.net

The next day when the Indians assembled they were told by the commissioners that all was ready and the treaty was laid upon a table and I found it just as the Indians had wanted it to be, except the description of the mile square. The part relating to the mile square that was to have been reserved for me read as follows:

“Chief Buffalo, being desirous of providing for some of his relatives who had rendered them important services, it is agreed that he may select one mile square of the ceded territory heretofore described.”

“Now,” said the commissioner,

“we want Buffalo to designate the person or persons to whom he wishes the patents to issue.”

Buffalo then said:

“I want them to be made out in the name of my adopted son.”

This closed all ceremony and the treaty was duly signed on the 30th day of September, 1854. This done the commissioners took a farewell shake of the hand with all the chiefs, hoping to meet them again at the annuity payment the coming year. They then boarded the steamer North Star for home. In the course of a few days the Indians also disappeared, some to their interior homes and some to their winter hunting grounds and a general quiet prevailed on the island.

Portrait of the Steamer North Star from American Steam Vessels, by Samuel Ward Stanton, page 40.

~ Wikimedia.org

About the second week in October, 1854, I went from La Pointe to Ontonagon in an open boat for the purpose of purchasing my winter supplies as it had got too late to depend on getting them from further below. While there a company was formed for the purpose of going into the newly ceded territory to make claims upon lands that would be subject to entry as soon as the late treaty should be ratified. The company consisted of Samuel McWaid, William Whitesides, W. W. Kingsbury, John Johnson, Oliver Melzer, John McFarland, Daniel S. Cash, W. W. Spaulding, all of Ontonagon, and myself. The two last named gentlemen, Daniel S. Cash and W. W. Spaulding, agreeing to furnish the company with supplies and all necessaries, including money, to enter the lands for an equal interest and it was so stipulated that we were to share equally in all that we, or either of us, might obtain. As soon as the supplies could be purchased and put aboard the schooner Algonquin we started for the head of the lake, stopping at La Pointe long enough for me to get my family aboard and my business matters arranged for the winter. I left my store at La Pointe in charge of Alex. Nevaux, and we all sailed for the head of Lake Superior, the site of which is now the city of Duluth. Reaching there about the first week in December—the bay of Superior being closed by ice—we were compelled to make our landing at Minnesota Point and take our goods from there to the main land on the north’ shore in open boats, landing about one and-one half miles east of Minnesota Point at a place where I desired to make a preemption for myself and to establish a trading post for the winter. Here I erected a building large enough for all of us to live in, as we expected to make this our headquarters for the winter, and also a building for a trading post. The other members of the company made claims in other places, but I did no more land looking that winter.

Detail of Superior City townsite at the head of Lake Superior from the 1854 U.S. General Land Office survey by Stuntz and Barber.

About January 20th, 1855, I left my place at the head of the lake to go back to La Pointe and took with me what furs I had collected up to that time, as I had a good place at La Pointe to dry and keep them. I took four men along to help me through and two dog trains. As we were passing down Superior Bay and when just in front of the village of West Superior a man came to us on the ice carrying a small bundle on his back and asked me if I had any objections to his going through in my company. He said the snow was deep and the weather cold and it was bad for one man to travel alone. I told him I had no objections provided he would take his turn with the other men in breaking the road for the dogs. We all went on together and camped that night at a place well known as Flag River. We made preparations for a cold night as the thermometer must have been twenty-five or thirty degrees below zero and the snow fully two feet deep. As there were enough of us we cut and carried up a large quantity of wood, both green and dry, and shoveled the snow away to the ground with our snow shoes and built a large fire. We then cut evergreen boughs and made a wind break or bough camp and concluded we could put in a very comfortable night. We then cooked and ate our supper and all seemed happy. I unrolled a bale of bear skins and spread them out on the ground for my bed, filled my pipe and lay down to rest while the five men with me were talking and smoking around the camp fire. I was very tired and presume I was not long in falling asleep. How long I slept I cannot tell, but was awakened by something dropping into my face, which felt like a powdered substance. I sprang to my feet for I found something had got into my eyes and was smarting them badly. I rushed for the snow bank that was melting from the heat and applied handful after handful to my eyes and face. I found the application was peeling the skin off my face and the pain soon became intense. I woke up the crew and they saw by the firelight the terrible condition I was in. In an hour’s time my eyeballs were so swollen that I could not close the lids and the pain did not abate. I could do nothing more than bathe my eyes until morning, which I did with tea-grounds. It seemed an age before morning came and when it did come I could not realize it, for I was totally blind. The party started with me at early dawn for La Pointe. The man who joined us the day before went no further, but returned to Superior, which was a great surprise to the men of our party, who frequently during the day would say:

“There is something about this matter that is not right,”

and I never could learn afterward of his having communicated the fact of my accident to any one or to assign any reason or excuse for turning back, which caused us to suspect that he had a hand in the blinding, but as I could get no proof to establish that suspicion, I could do nothing in the matter. This man was found dead in his cabin a few months afterwards.

At La Pointe I got such treatment as could be procured from the Indians which allayed the inflamation but did not restore the sight. I remained at La Pointe about ten days, and then returned home with dog train to my family, where I remained the balance of the winter, when not at Superior for treatment. When the ice moved from the lake in the spring I abandoned everything there and returned to La Pointe and was blind or nearly so until the winter of 1861.

Returning a little time to the north shore I wish to relate an incident of the death of one of our Ontonagon company. Two or three days after I had reached home from La Pointe, finding my eyes constantly growing worse I had the company take me to Superior where I could get treatment. Dr. Marcellus, son of Prof. Marcellus, of an eye infirmary in Philadelphia, who had just then married a beautiful young wife, and come west to seek his fortune, was engaged to treat me. I was taken to the boarding house of Henry Wolcott, where I engaged rooms for the winter as I expected to remain there until spring. I related to the doctor what had befallen me and he began treatment. At times I felt much better but no permanent relief seemed near. About the middle February my family required my presence at home, as there was some business to be attended to which they did not understand. My wife sent a note to me by Mr. Melzer, stating that it was necessary for me to return, and as the weather that day was very pleasant, she hoped that I would come that afternoon. Mr. Melzer delivered me the note, which I requested him to read. It was then 11 a. m. and I told him we would start right after dinner, and requested him to tell the doctor that I wished to see him right away, and then return and get his dinner, as it would be ready at noon, to which he replied:

“If I am not here do not wait for me, but I will be here at the time you are ready for home.”

Mr. Melzer did return shortly after we had finished our dinner and I requested him to eat, as I would not be ready to start for half an hour, but he insisted he was not hungry. We had no conveyance and at 1 p. m. we set out for home. We went down a few steps to the ice, as Mr. Wolcott’s house stood close to the shore of the bay, and went straight across Superior Bay to Minnesota Point, and across the point six or eight rods and struck the ice on Lake Superior. A plain, hard beaten road led from here direct to my home. After we had proceeded about 150 yards, following this hard beaten road, Melzer at once stopped and requested me to go ahead, as I could follow the beaten road without assistance, the snow being deep on either side.

“Now,” he says go ahead, for I must go back after a drink.”

I followed the road quite well, and when near the house my folks came out to meet me, their first inquiry being:

“Where is Melzer?”

I told them the circumstances of his turning back for a drink of water. Reaching the bank on which my house stood, some of my folks, looking back over the road I had come, discovered a dark object apparently floundering on the ice. Two or three of our men started for the spot and there found the dead body of poor Melzer. We immediately notified parties in Superior of the circumstances and ordered a post-mortem examination of the body. The doctors found that his stomach was entirely empty and mostly gone from the effects of whisky and was no thicker than tissue paper and that his heart had burst into three pieces. We gave him a decent burial at Superior and peace to his ashes, His last act of kindness was in my behalf.

To be continued in Chapter III…

Early Life among the Indians: Chapter I

September 26, 2017

By Amorin Mello

Early Life among the Indians

by Benjamin Green Armstrong

Early Indian History.

—

CHAPTER I.

—

The First Treaty.—The Removal Order.— Treaties of 1837 and 1842.—A Trip to Washington.—In New York City with Only One Dime.—At the Broker’s Residence.

My earliest recollections in Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota territories date back to 1835, at which time Gen. Cass and others on the part of the Government, with different tribes of Indians, viz : Potawatomies, Winnebagos, Chippewas, Saux and Foxes and the Sioux, at Prairie du Chien, met in open council, to define and agree upon boundary lines between the Saux and Foxes and the Chippewas. The boundary or division of territory as agreed upon and established by this council was the Mississippi River from Prairie du Chien north to the mouth of of Crow Wing River, thence to its source. The Saux and Foxes and the Sioux were recognized to be the owners of all territory lying west of the Mississippi and south of the Crow Wing River. The Chippewas, by this treaty, were recognized as the owners of all lands east of the Mississippi in the territory of Wisconsin and Minnesota, and north of the Crow Wing River on both sides of the Mississippi to the British Possessions, also Lake Superior country on both sides of the lake to Sault Ste. Marie and beyond. The other tribes mentioned in this council had no interest in the above divided territory from the fact that their possessions were east and south of the Chippewa Country, and over their title there was no dispute. The division lines were agreed to as described and a treaty signed. When all shook hands and covenanted with each other to live in peace for all time to come.

In 1837 the Government entered into a treaty with the Chippewas of the Mississippi and St. Croix Rivers at St. Peter, Minnesota, Col. Snelling, of the army, and Maj. Walker, of Missouri, being the commissioners on the part of the Government, and it appears that at the commencement of this council the anxiety on the part of the commissioners to perfect a treaty was so great that statements were made by them favorable to the Indians, and understood perfectly by them, that were not afterwards incorporated in the treaty. The Indians were told by these commissioners that the great father had sent them to buy their pine timber and their minerals that were hidden in the earth, and that the great father was very anxious to dig the mineral, for of such material he made guns and knives for the Indians, and copper kettles in which to boil their sugar sap.

“The timber you make but little use of is the pine your great father wants to build many steamboats, to bring your goods to you and to take you to Washington bye-and-bye to see your great father and meet him face to face. He does not want your lands, it is too cold up here for farming. He wants just enough of it to build little towns where soldiers stop, mining camps for miners, saw mill sites and logging camps. The timber that is best for you the great father does not care about. The maple tree that you make your sugar from, the birch tree that you get bark from for your canoes and from which you make pails for your sugar sap, the cedar from which you get material for making canoes, oars and paddles, your great father cares nothing for. It is the pine and minerals that he wants and he has sent us here to make a bargain with you for it,” the commissioners said.

And further, the Indians were told and distinctly understood that they were not to be disturbed in the possession of their lands so long as their men behaved themselves. They were told also that the Chippewas had always been good Indians and the great father thought very much of them on that account, and with these promises fairly and distinctly understood they signed the treaty that ceded to the government all their territory lying east of the Mississippi, embracing the St. Croix district and east to the Chippewa River, but to my certain knowledge the Indians never knew that they had ceded their lands until 1849, when they were asked to remove therefrom.

Robert Stuart was an American Fur Company agent and Acting Superintendent on Mackinac Island.

~ Wikipedia.org

In 1842 Robert Stewart, on the part of the government, perfected a treaty at La Pointe, on Lake Superior, in which the Chippewas of the St. Croix and Superior country ceded all that portion of their territory, from the boundary of the former treaty of 1837, with the Chippewas of the Mississippi and St. Croix Indians, east and along the south shore of the lake to the Chocolate River, Michigan, territory. No conversation that was had at this time gave the Indians an inkling or caused them to mistrust that they were ceding away their lands, but supposed that they were simply selling the pine and minerals, as they had in the treaty of 1837, and when they were told, in 1849, to move on and thereby abandon their burying grounds — the dearest thing to an Indian known— they began to hold councils and to ask each as to how they had understood the treaties, and all understood them the same, that was : That they were never to be disturbed if they behaved themselves. Messengers were sent out to all the different bands in every part of their country to get the understanding of all the people, and to inquire if any depredations had been committed by any of their young men, or what could be the reason for this sudden order to move. This was kept up for a year, but no reason could be assigned by the Indians for the removal order.

The treaty of 1842 made at La Pointe stipulated that the Indians should receive their annuities at La Pointe for a period of twenty-five years. Now by reason of a non-compliance with the order to move away, the annuity payment at La Pointe had been stopped and a new agency established at Sandy Lake, near the Mississippi River, and their annuities taken there, and the Indians told to go there for them, and to bring along their women and children, and to remain there, and all that did not would be deprived of their pay and annuities.

In the fall of 1851, and after all the messengers had returned that had been sent out to inquire after the cause for the removal orders, the chiefs gathered in council, and after the subject had been thoroughly canvassed, agreed that representatives from all parts of the country should be sent to the new agency and see what the results of such a visit would be. A delegation was made up, consisting of about 500 men in all. They reached the new agency about September 10th of that year. The agent there informed them that rations should be furnished to them until such time as he could get the goods and money from St. Paul.

Some time in the latter part of the month we were surprised to hear that the new agency had burned down, and, as the word came to us,

“had taken the goods and money into the ashes.”

The agent immediately started down the river, and we saw no more of him for some time. Crowds of Indians and a few white men soon gathered around the burnt remains of the agency and waited until it should cool down, when a thorough search was made in the ashes for melted coin that must be there if the story was true that goods and money had gone down together. They scraped and scratched in vain All that was ever found in that ruin in the shape of metal was two fifty cent silver pieces. The Indians, having no chance to talk with the agent, could find out nothing of which they wished to know. They camped around the commissary department and were fed on the very worst class of sour, musty pork heads, jaws, shoulders and shanks, rotten corned beef and the poorest quality of flour that could possibly be milled. In the course of the next month no fewer than 150 Indians had died from the use of these rotten provisions, and the remainder resolved to stay no longer, and started back for La Pointe.

At Fond du Lac, Minnesota, some of the employees of the American Fur Co. urged the Indians to halt there and wait for the agent to come, and finally showed them a message from the agent requesting them to stop at Fond du Lac, and stated that he had procured money and goods and would pay them off at that point, which he did during the winter of 1851. About 500 Indians gathered there and were paid, each one receiving four dollars in money and a very small goods annuity. Before preparing to leave for home the Indians wanted to know of the agent, John S. Waters, what he was going to do with the remainder of the money and goods. He answered that he was going to keep it and those who should come there for it would get their share and those that did not would get nothing. The Indians were now thoroughly disgusted and discouraged, and piling their little bundles of annuity goods into two piles agreed with each other that a game of lacrosse should be played on the ice for the whole stock. The Lake Superior Indians were to choose twenty men from among them and the interior Indians the same number. The game was played, lasting three days, and resulting in a victory for the interiors. During all this time councils were being held and dissatisfaction was showing itself on every hand. Threats were freely indulged in by the younger and more resolute members of the band, who thought while they tamely submitted, to outrage their case would never grow better. But the older and more considerate ones could not see the case as they did, but all plainly saw there was no way of redress at present and they were compelled to put up with just such treatment as the agent saw fit to inflict upon them. They now all realized that they had been induced to sign treaties that they did not understand, and had been imposed upon. They saw that when the annuities were brought and they were asked to touch the pen, they had only received what the agent had seen fit to give them, and certainly not what was their dues. They had lost 150 warriors on this one trip alone by being fed on unwholesome provisions, and they reasoned among themselves :

Is this what our great father intended? If so we may as well go to our old home and there be slaughtered where we can be buried by the side of our relatives and friends.

These talks were kept up after they had returned to La Pointe. I attended many of them, and being familiar with the language, I saw that great trouble was brewing and if something was not quickly done trouble of a serious nature would soon follow. At last I told them if they would stop where they were I would take a party of chiefs, or others, as they might elect, numbering five or six, and go to Washington, where they could meet the great father and tell their troubles to his face. Chief Buffalo and other leading chieftains of the country at once agreed to the plan, and early in the spring a party of six men were selected, and April 5th, 1852, was appointed as the day to start. Chiefs Buffalo and O-sho-ga, with four braves and myself, made up the party. On the day of starting, and before noon, there were gathered at the beach at old La Pointe, Indians by the score to witness the departure. We left in a new birch bark canoe which was made for the occasion and called a four fathom boat, twenty-four feet long with six paddles. The four braves did most of the paddling, assisted at times by O-sho-ga and sometimes by Buffalo. I sat at the stern and directed the course of the craft. We made the mouth of the Montreal River, the dividing line between Wisconsin and Michigan, the first night, where we went ashore and camped, without covering, except our blankets. We carried a small amount of provisions with us, some crackers, sugar and coffee, and depended on game and fish for meat. The next night, having followed along the beach all day, we camped at Iron River. No incidents of importance happened, and on the third day out from La Pointe, at 10 a. m. we landed our bark at Ontonagon, where we spent two days in circulating a petition I had prepared, asking that the Indians might be left and remain in their own country, and the order for their removal be reconsidered. I did not find a single man who refused to sign it, which showed the feeling of the people nearest the Indians upon the subject. From Ontonagon we went to Portage Lake, Houghton and Hancock, and visited the various copper mines, and all there signed the petition. Among the signers I would occasionally meet a man who claimed personal acquaintance with the President and said the President would recognize the signature when he saw it, which I found to be so on presenting the petition to President Filmore. Among them was Thomas Hanna, a merchant at Ontonagon, Capt. Roberts, of the Minnesota mine, and Douglas, of the firm of Douglas & Sheldon, Portage Lake. Along the coast from Portage Lake we encountered a number of severe storms which caused us to go ashore, and we thereby lost considerable time. Stopping at Marquette I also circulated the petition and procured a great many signatures. Leaving there nothing was to be seen except the rocky coast until we reached Sault Ste. Marie, where we arrived in the afternoon and remained all the next day, getting my petition signed by all who were disposed. Among others who signed it was a Mr. Brown, who was then editing a paper there. He also claimed personal acquaintance with the President and gave me two or three letters of introduction to parties in New York City, and requested me to call on them when I reached the city, saying they would be much pleased to see the Indian chieftains from this country, and that they would assist me in case I needed assistance, which I found to be true.

The second day at the “Soo” the officers from the fort came to me with the inteligence that no delegation of Indians would be allowed to go to Washington without first getting permission from the government to do so, as they had orders to stop and turn back all delegations of Indians that should attempt to come this way en-route to Washington. This was to me a stunner. In what a prediciment I found myself. To give up this trip would be to abandon the last hope of keeping that turbulent spirit of the young warriors within bounds. Now they were peacably inclined and would remain so until our mission should decide their course. They were now living on the hope that our efforts would obtain for them the righting of a grievous wrong, but to return without anything accomplished and with the information that the great father’s officers had turned us back would be to rekindle the fire that was smoldering into an open revolt for revenge. I talked with the officers patiently and long and explained the situation of affairs in the Indian country, and certainly it was no pleasant task for me to undertake, without pay or hope of reward, to take this delegation through, and that I should never have attempted it if I had not considered it necessary to secure the safety of the white settlers in that country, and that although I would not resist an officer or disobey an order of the government, I should go as far as I could with my Indians, and until I was stopped by an officer, then I would simply say to the Indians,

“I am prevented from going further. I have done all I can. I will send you as near home, as I can get conveyances for you, but for the present I shall remain away from that country,”

The officers at the “Soo” finally told me to go on, but they said,

“you will certainly be stopped at some place, probably at Detroit. The Indian agent there and the marshall will certainly oppose your going further.”

More than one Steamer Northerner was on the Great Lakes in 1852. This may have been the one Chief Buffalo’s delegation rode on.

~ Great Lakes Maritime Database

But I was determined to try, and as soon as I could get a boat for Detroit we started. It was the steamer Northerner, and when we landed in Detroit, sure enough, we were met by the Indian agent and told that we could go no further, at any rate until next day, or until he could have a talk with me at his office. He then sent us to a hotel, saying he would see that our bill was paid until next day. About 7:30 that evening I was called to his office and had a little talk with him and the marshall. I stated to them the facts as they existed in the northwest, and our object in going to Washington, and if we were turned back I did not consider that a white man’s life would long be safe in the Indian country, under the present state of excitement; that our returning without seeing the President would start a fire that would not soon be quenched. They finally consented to my passing as they hardly thought they could afford to arrest me, considering the petitions I had and the circumstances I had related.

“But,” they also added, “we do not think you will ever reach Washington with your delegation.”

I thanked them for allowing us to proceed and the next morning sailed for Buffalo, where we made close connections with the first railroad cars any of us had ever seen and proceeded to Albany, at which place we took the Steamer Mayflower, I think. At any rate the boat we took was burned the same season and was commanded by Capt. St. John.

Lecture Room (theater) at Barnum’s American Museum circa 1853.

~ Commons.Wikimedia.org

We landed in New York City without mishap and I had just and only one ten-cent silver piece of money left. By giving the ‘bus driver some Indian trinkets I persuaded him to haul the party and baggage to the American House, which then stood a block or so from Barnum’s Theatre. Here I told the landlord of my financial embarrassment and that we must stay over night at any rate and in some way the necessary money to pay the bill should be raised. I found this landlord a prince of good fellows and was always glad that I met him. I told him of the letters I had to parties in the city and should I fail in getting assistance from them I should exhibit my fellows and in this way raise the necessary funds to pay my bill and carry us to our destination. He thought the scheme a good one, and that himself and me were just the ones to carry it out. Immediately after supper I started out in search of the parties to whom I had letters of introduction, and with the landlord’s help in giving me directions, I soon found one of them, a stock broker, whose name I cannot remember, or the street on which he lived. He returned with me to the hotel, and after looking the Indians over, he said,

“You are all right. Stay where you are and I will see that you have money to carry you through.”

The next day I put the Indians on exhibition at the hotel, and a great many people came to see them, most of whom contributed freely to the fund to carry us to our destination. On the second evening of the exhibition this stock broker came with his wife to the show, and upon taking his leave, invited me to bring the delegation to his house the next afternoon, where a number of ladies of their acquaintance could see them without the embarrassment they would feel at the show room. To this I assented, and the landlord being present, said he would assist by furnishing tho conveyance. But when the ‘bus was brought up in front of the house the next day for the purpose of taking the Indians aboard, the crowd became so dense that it was found impossible to get them into it, and it was with some difficulty that they were gotten back to their room. We saw it would not be possible to get them across the city on foot or by any method yet devised. I despatched a note to the broker stating how matters stood, and in less than half an hour himself and wife were at the hotel, and the ready wit of this little lady soon had a plan arranged by which the Indians could be safely taken from the house and to her home without detection or annoyance. The plan was to postpone the supper she had arranged for in the afternoon until evening, and that after dark the ‘bus could be placed in the alley back of the hotel and the Indians got into it without being observed. The plan was carefully carried out by the landlord. The crowd was frustrated and by 9 p. m. we were whirling through the streets with shaded ‘bus windows to the home of the broker, which we reached without any interruption, and were met at the door by the little lady whose tact had made the visit possible, and I hope she may now be living to read this account of that visit, which was nearly thirty-nine years ago. We found some thirty or forty young people present to see us, and I think a few old persons. The supper was prepared and all were anxious to see the red men of the forest at a white man’s table. You can imagine my own feelings on this occasion, for, like the Indians, I had been brought up in a wilderness, entirely unaccustomed to the society of refined and educated people, and here I was surrounded by them and the luxuries of a finished home, and with the conduct of my wards to be accounted for, I was forced to an awkward apology, which was, however, received with that graciousness of manner that made me feel almost at home. Being thus assured and advised that our visit was contemplated for the purpose of seeing us as nearly in our native ways and customs as was possible, and that no offense would be taken at any breach of etiquette, but, on the contrary, they should be highly gratified if we would proceed in all things as was our habit in the wilderness, and the hostess, addressing me, said it was the wish of those present that in eating their supper the Indians would conform strictly to their home habits, to insure which, as supper was then being put in readiness for them, I told the Indians that when the meal had been set before them on the table, they should rise up and pushing their chairs back, seat themselves upon the floor, taking with them only the plate of food and the knife. They did this nicely, and the meal was taken in true Indian style, much to the gratification of the assemblage. When the meal was completed each man placed his knife and plate back upon the table, and, moving back towards the walls of the room, seated himself upon the floor in true Indian fashion.

As the party had now seen enough to furnish them with tea table chat, they ate their supper and after they had finished requested a speech from the Indians, at least that each one should say something that they might hear and which I could interpret to the party. Chief O-sha-ga spoke first, thanking the people for their kindness. Buffalo came next and said he was getting old and was much impressed by the manner of white people and showed considerable feeling at the nice way in which they had been treated there and generally upon the route.

Our hostess, seeing that I spoke the language fluently, requested that I make them a speech in the Chippewa tongue. To do this so they would understand it best I told them a story in the Indian tongue. It was a little story about a monkey which I had often told the Indians at home and it was a fable that always caused great merriment among them, for a monkey was, in their estimation, the cutest and most wonderful creature in the world, an opinion which they hold to the present time. This speech proved to be the hit of the evening, for I had no sooner commenced (though my conversation was directed to the white people), than the Indians began to laugh and cut up all manner of pranks, which, combined with the ludicrousness of the story itself, caused a general uproar of laughter by all present and once, if never again, the fashionably dressed and beautiful ladies of New York City vied with each other and with the dusky aborigines of the west in trying to show which one of all enjoyed best the festivities. The rest of the evening and until about two o’clock next morning was spent in answering questions about our western home and its people, when we returned to the hotel pleased and happy over the evening’s entertainment.

To be continued in Chapter II…

The Removal Order of 1849

March 12, 2016

By Amorin Mello

United States. Works Progress Administration:

Chippewa Indian Historical Project Records 1936-1942

(Northland Micro 5; Micro 532)

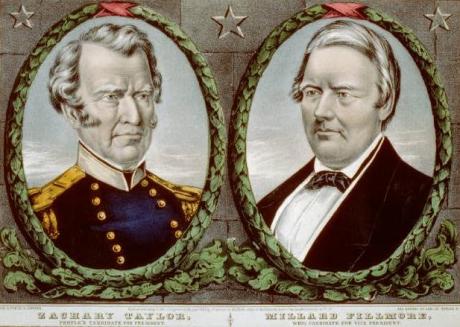

12th President Zachary Taylor gave the 1849 Removal Order while he was still in office. During 1852, Chief Buffalo and his delegation met 13th President Millard Fillmore in Washington, D.C., to petition against this Removal Order.

~ 1848 presidential campaign poster from the Library of Congress

Reel 1; Envelop 1; Item 14.

The Removal Order of 1849

By Jerome Arbuckle

After the war of 1812 the westward advance of the people of the United States of was renewed with vigor. These pioneers were imbued with the idea that the possessions of the Indian tribes, with whom they came in contact, were for their convenience and theirs for the taking. Any attempt on the part of the aboriginal owners to defend their ancestral homes were a signal for a declaration of war, or a punitive expedition, which invariably resulted in the defeat of the Indians.

“Peace Treaties,” incorporating terms and stipulations suitable particularly to the white man’s government, were then negotiated, whereby the Indians ceded their lands, and the remnants of the dispossessed tribe moved westward. The tribes to the south of the Great Lakes, along the Ohio Valley, were the greatest sufferers from this system of acquisition.

Another system used with equal, if less sanguinary success, was the “treaty system.” Treaties of this type were actually little more than receipt signed by the Indian, which acknowledged the cessions of huge tracts of land. The language of the treaties, in some instances, is so plainly a scheme for the dispossession and removal of the Indians that it is doubtful if the signers for the Indians understood the true import of the document. Possibly, and according to the statements handed down from the Indians of earlier days to the present, Indians who signed the treaties were duped and were the victims of treachery and collusion.

By the terms of the Treaties of 1837 and 1842, the Indians ceded to the Government all their territory lying east of the Mississippi embracing the St. Croix district and eastward to the Chocolate River. The Indians, however, were ignorant of the fact that they had ceded these lands. According to the terms, as understood by them, they were permitted to remain within these treaty boundaries and continue to enjoy the privileges of hunting, fishing, ricing and the making of maple sugar, provided they did not molest their white neighbors; but they clearly understood that the Government was to have the right to use the timber and minerals on these lands.

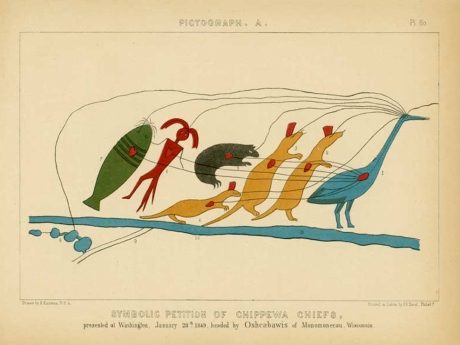

Entitled “Chief Buffalo’s Petition to the President“ by the Wisconsin Historical Society, the story behind this now famous symbolic petition is actually unrelated to Chief Buffalo from La Pointe, and was created before the Sandy Lake Tragedy. It is a common error to mis-attribute this to Chief Buffalo’s trip to Washington D.C., which occurred after that Tragedy. See Chequamegon History’s original post for more information.

Detail of Benjamin Armstrong from a photograph by Matthew Brady (Minnesota Historical Society). See our Armstrong Engravings post for more information.

Their eyes were opened when the Removal Order of 1849 came like a bolt from the blue. This order cancelled the Indians’ right to hunt and fish in the territory ceded, and gave notification for their removal westward. According to Verwyst, the Franciscan Missionary, many left by reason of this order, and sought a refuge among the westernmost of their tribe who dwelt in Minnesota.

Many of the full bloods, who naturally had a deep attachment for their home soil, refused to budge. The chiefs who signed the treaty were included in this action. They then concluded that they were duped by the Treaty Commissioners and were given a faulty interpretation of the treaty passages. Although the Chippewa realized the futility of armed resistance, those who chose to remain unanimously decided to fight it out. A few white men who were true friends of the Indians, among these was Ben Armstrong, the adopted son of the Head Chief, Buffalo, and he cautioned the Indians against any show of hostility.

At a council, Armstrong prevailed upon the chiefs to make a trip to Washington. Accordingly, preparations for the trip were made, a canoe of special make being constructed for the journey. After cautioning the tribesmen to remain calm, pending their return, they set out for Washington in April, 1852. The party was composed of Buffalo, the head Chief, and several sub-chiefs, one of whom was Oshoga, who later became a noted man among the Chippewa. Armstrong was the interpreter and director of the party. The delegation left La Pointe and proceeded by way of the Great Lakes as far as Buffalo, N. Y., and then by rail to Washington. They stopped at the white settlements along the route and their leader, Mr. Armstrong, circulated a petition among the white people. This petition, which was to be presented to the President, urged that the Chippewa be permitted to remain in their own country and the Removal Order reconsidered. Many signatures were obtained, some of the signers being acquaintances of the President, whose signatures he later recognized.

Despite repeated attempts of arbitrary agents, who were employed by the government to administer Indian affairs, and who endeavored to return them back or discourage the trip, they resolutely persisted. The party arrived at Buffalo, New York, practically penniless. By disposing of some Indian trinkets, and by putting the chief on exhibition, they managed to acquire enough money to defray their expenses until they finally arrived at Washington.

Here it seemed their troubles were to begin. They were refused an audience with those persons who might have been able to assist them. Through the kind assistance of Senator Briggs of New York, they eventually managed to arrange for an interview with President Fillmore.

United States Representative George Briggs was helpful in getting an audience with President Millard Fillmore.

~ Library of Congress

At the appointed time they assembled for the interview and after smoking the peace pipe offered by Chief Buffalo, the “Great White Father” listened to their story of conditions in the Northwest. Their petition was presented and read and the meeting adjourned. President Fillmore, deeply impressed by his visitors, directed that their expenses should be paid by the Government and that they should have the freedom of the city for a week.

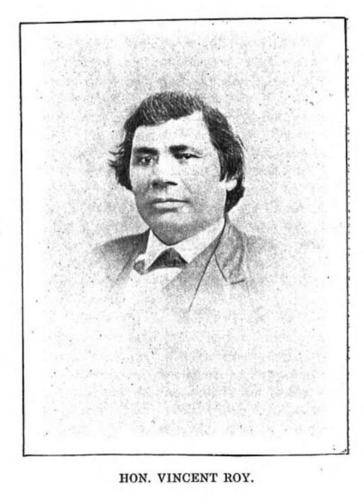

![Vincent Roy, Jr., portrait from "Short biographical sketch of Vincent Roy, [Jr.,]" in Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476.](https://chequamegonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/vincent-roy-jr.jpg?w=219&h=300)

Vincent Roy, Jr., was also on this famous trip to Washington, D.C. For more information, see this excerpt from Vincent Roy Jr’s biography.

Their mission was accomplished and all were happy. They had achieved what they sought. An uprising of their people had been averted in which thousands of human lives might have been cruelly slaughtered; so with light hearts they prepared for their homeward trip. Their fare was paid and they returned by rail by way of St. Paul, Minnesota, which was as near as they could get by rail to their homes. From St. Paul they traveled overland, a distance of over two hundred miles, overland. Along the route they frequently met with bands of Chippewa, whom they delighted with the information of the successes of their trip. These groups they instructed to repair to Madeline Island for the treaty at the time stipulated.

Upon their arrival at their own homes, the successes of the delegation was hailed with joy. Runners were dispatched to notify the entire Chippewa nation. As a consequence, many who had left their homes in compliance with the Removal Order now returned.

When the time for the treaty drew near, the Chippewa began to arrive at the Island from all directions. Finally, after careful deliberations, the treaty of 1854 was concluded. This treaty provided for several reservations within the ceded territory. These were Ontonagon and L’Anse, in the present state of Michigan, Lac du Flambeau, Bad River or La Pointe, Red Cliff, and Lac Courte Oreille, in Wisconsin, and Fond du Lac and Grand Portage in Minnesota.

It was at this time that the Chippewa mutually agreed to separate into two divisions, making the Mississippi the dividing line between the Mississippi Chippewa and the Lake Superior Chippewa, and allowing each division the right to deal separately with the Government.

Biographical Sketch of Vincent Roy, Jr.

March 3, 2016

By Amorin Mello

Portrait of Vincent Roy, Jr., from “Short biographical sketch of Vincent Roy,” in Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, by Chrysostom Verwyst, 1900, pages 472-476.

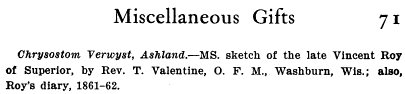

Miscellaneous materials related to Vincent Roy,

1861-1862, 1892, 1921

Wisconsin Historical Society

“Miscellaneous items related to Roy, a fur trader in Wisconsin of French and Chippewa Indian descent including a sketch of his early years by Reverend T. Valentine, 1896; a letter to Roy concerning the first boats to go over the Sault Ste. Marie, 1892; a letter to Valentine regarding an article on Roy; an abstract and sketch on Roy’s life; a typewritten copy of a biographical sketch from the Franciscan Herald, March 1921; and a diary by Roy describing a fur trading journey, 1860-1861, with an untitled document in the Ojibwe language (p. 19 of diary).”

Reuben Gold Thwaites was the author of “The Story of Chequamegon Bay”.

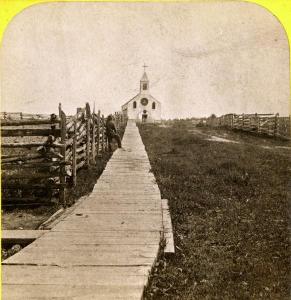

St. Agnes’ Church

205 E. Front St.

Ashland, Wis., June 27 1903

Reuben G. Thwaites

Sec. Wisc. Hist Soc. Madison Wis.

Dear Sir,